[Tiffany Wayne is a historian of

women, gender, and feminism and the author or editor of eight published works

in U.S. history, women’s history, and literary studies. The following post is

drawn from a paper presented at the Western Association of Women Historians

conference, Costa Mesa, California, Spring 2022, and is part of ongoing

research for a forthcoming book project, Suffrage Road Trip: Three Women, Three Thousand Miles, and a Meeting with the President, the story of the suffrage envoys who drove from the 1915 world’s fair in San Francisco to Washington, D.C. to deliver a signed petition demanding a federal suffrage amendment directly into the hands of President Woodrow Wilson. You can follow her work here.]

On

the evening of Thursday, September 16th, 1915, under a “bright-starred,

deep-blue California sky,” more than 10,000 visitors to the San Francisco

Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) gathered in Golden Gate Park to

send three suffragists off on an epic cross-country road trip. The suffrage

envoys on center stage that evening were Sara Bard Field, by 1915 already a

veteran of several western state suffrage campaigns in California, Oregon, and

Nevada, and Maria Kindberg and Ingeborg Kindstedt, two Swedish-American

suffragists from Rhode Island who owned the brand-new Overland car and knew how

to both drive and maintain an automobile. Another prominent national suffrage

organizer, Mabel Vernon, traveled by train ahead of the car and connected with

local suffrage chapters to set up events, parades, and meetings with mayors and

other dignitaries in every major city the envoys visited and, most importantly,

to make sure their activities received extensive press coverage. Between

September and December 1915 they drove through 21 states from San Francisco to

Washington, D.C. with the end goal of hand-delivering to President Woodrow

Wilson a petition of signatures gathered in support of a simple message: We

demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, enfranchising

women.

At

the celebratory send-off at the fair’s Court of Abundance, a procession of

young women dressed in the traditional costumes of Norway, Finland, and other

nations where women already exercised the right to vote, spotlighted how the

United States lagged behind in the international progress of suffrage. By 1915, women had full

voting rights in Finland, Norway, Denmark, Latvia, Australia, and New Zealand,

and American women could vote in eleven states, all in the West: Wyoming

(1890), Colorado (1893), Utah and Idaho (both in 1896), Washington (1910),

California (1911), Arizona, Oregon, and Kansas (all in 1912), and Montana and

Nevada (both in 1914). But the denial of voting rights to any U.S.

citizens was an embarrassment to a democratic nation trying to display its strength

and innovation on the world stage, both at the fair and soon to be abroad in

world war. Stretched across the Congressional Union booth at the Expo, a banner

reminded visitors: “The world has progressed in most ways, but not yet in its

recognition of women.”

The

three women, empowered by their powerful purpose, then drove away from the

Expo, a choir singing and the crowd waving goodbye:

Orange

lanterns swayed in the breeze; purple, white and gold draperies fluttered, the

blare of the band burst forth, and the great surging crowd followed to the

gates...Cheers burst forth as the gates opened and the big car swung through,

ending the most dramatic and significant suffrage convention that has probably

ever been held in the history of the world.

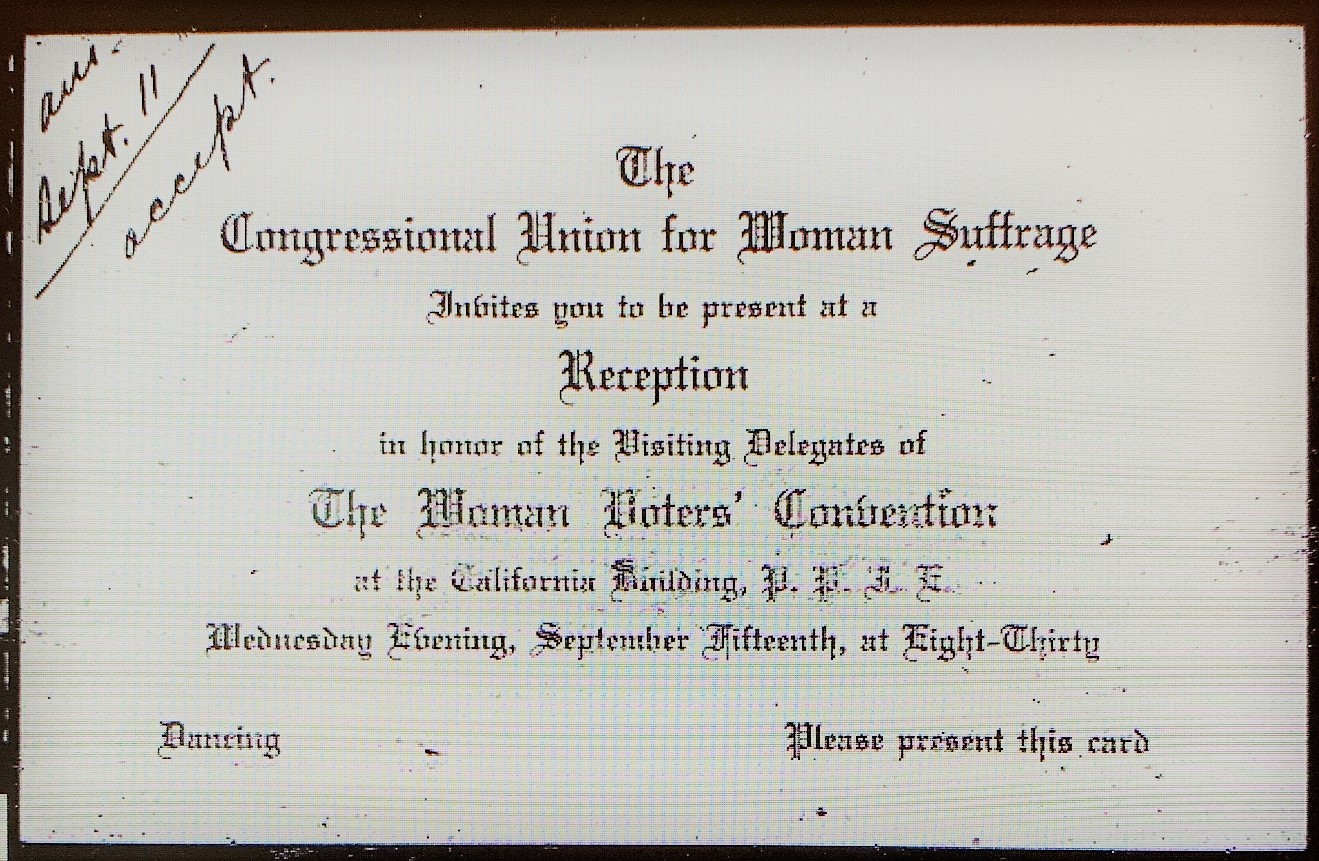

The

gathering in San Francisco on that evening in September 1915 was the

culmination of a three-day Woman Voters’ Convention, sponsored by the

Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), a committee of the National

American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and led by Alice Paul. This was the

first convention to emphasize the voices and collective power of now four

million women voters in the United States, a number the suffragists repeated

again and again in the press coverage. California was still fresh from a

suffrage victory in 1911 and the Congressional Union planned to capitalize on

this fact at the Expo by emphasizing that enfranchised western women were no

longer asking men for the vote, they were demanding it based on

their own political power at the polls.

The

send-off of the road trip envoys on the final night of the Woman Voters’

Convention was a highly publicized and carefully orchestrated spectacle, but it

was the culmination of a nearly year-long presence of the Congressional Union

at the (PPIE). Amidst the escalating international crisis of world war, San

Francisco hosted 18 million visitors between February and December 1915 to “The

Jewel City,” the theme of the PPIE. Like California itself, the Panama-Pacific

International Exposition was a celebration of the future – of new ideas and new

technologies, of progress - and, specifically, a celebration of the opening of

the Panama Canal. The United States had not yet entered into the world

conflict, but the women’s movement was already made up of international

alliances as many prominent American suffragists also worked as pacifists in

support of international human rights and peace. In 1915, the same year of the

PPIE, the Woman’s Peace Party was founded by Jane Addams, Carrie Chapman Catt

(president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association), and others. On

June 5, 1915, five hundred women participated in the “Pageant of Peace” at the

Expo, and the International Conference of Women Workers to Promote Permanent

Peace (ICWWPPP) held their convention there that summer as well.

While

many suffragists worked simultaneously for the vote and for peace during the

war years, the emphasis for the Congressional Union at the 1915 PPIE was a

permanent booth at the Palace of Education and Social Economy to promote their

singular goal: a federal suffrage amendment. And the San Francisco Expo was the

first time that women’s suffrage had its own focus and booth at a

world’s fair.

Previous world’s fairs held in the

United States – the Centennial Exposition (Philadelphia, 1876), World's

Industrial and Cotton Centennial (New Orleans, 1884), World’s Columbian

Exposition (Chicago, 1893), and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis,

1904) – had been important sites for highlighting women’s contributions across

a variety of fields and causes. Unlike some of these previous fairs, however,

there was no dedicated “Woman’s Building” at the PPIE in San Francisco; rather,

politically-engaged suffragists, peace advocates, temperance activists, and a

variety of women’s professional and educational organizations and clubs were

active throughout the Expo. Envoy Sara Bard Field acknowledged the wider role

of women throughout the fair, beyond the suffrage booth, noting that “One need

not be a fanatical feminist to see the persistent permeation of the essentially

feminine in every exhibit in this Palace of Progress.” There were exhibits by

the National Council of Jewish Women, the American Federation of Labor (noting

that “eight million working women of the land need the vote”), and the presence

at the fair of other consumer and reform committees led by women. As a

pacifist, Field happily concluded that the only place in the entire fair where

women were happily not represented was in exhibits related to war and

the military.

Preparing for the Expo

By late 1914, plans were already

underway for a suffrage booth at the PPIE, and the Congressional Union began

fundraising for and publicizing the booth in the months before the exposition

opened in February. Alice Paul sent fundraising letters to CU members and

contacts, explaining that money was needed to purchase “literature, banners,

placards, and all kinds of exhibits of a propagandistic nature, and finally to

pay a suffrage worker to remain in charge of [the booth] and explain the

suffrage situation to passers-by, to hold meetings, etc.” That salaried suffrage

worker was Margaret Fay Whittemore, chair of the CU in Michigan, who was paid

$70 a month to direct the booth in San Francisco from February to May. Paul

explained to potential donors that “The booth is the only place that suffrage

will be presented at the Exposition and it seems imperative

that the opportunity which the Exposition opens to us should not be lost.” The PPIE officially

opened on February 20, 1915 and booth leader Whittemore reported to Alice Paul

that an “enthusiastic deputation of San Francisco Congressional Union Member[s]

marched” in the grand opening parade “wearing the colors,” i.e. the purple, white,

and gold of the suffrage movement.

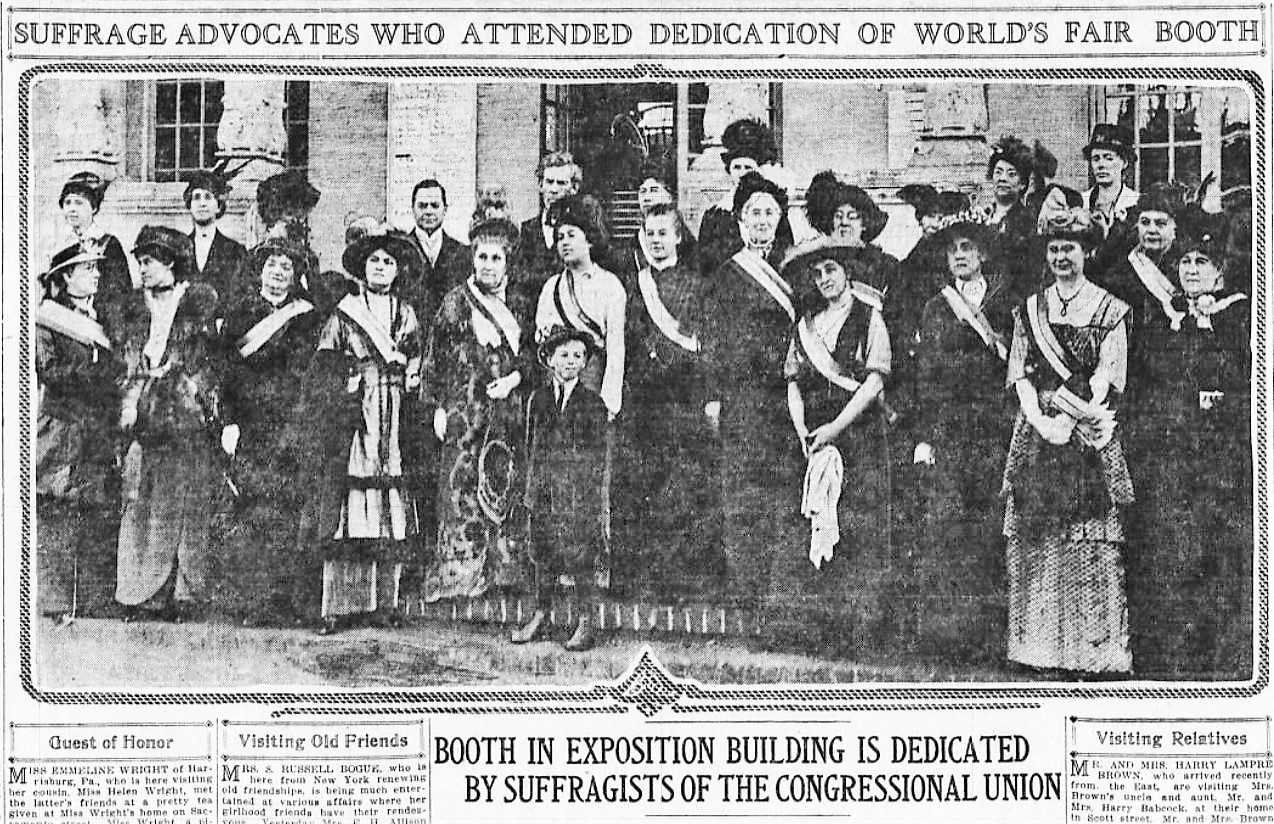

Opening Day

The official dedication of the suffrage booth at the PPIE happened a few weeks later, on March 4th, 1915, with a large gathering of speakers and then a reception at the booth itself which was “all dressed up in C.U. colors, flags and flowers.” Whittemore presented “a brief review of the actual things accomplished by the Union in the [past] two years,” followed by a speech by Gail Laughlin, a Maine suffragist and lawyer who eventually moved west and was active in the Colorado and California

campaigns, who “gave a most powerful address on the Federal amendment…and a great deal in regard to the objections of all politicians on the grounds of states rights.”

The goal of suffragists at the PPIE throughout 1915 was to create an attractive booth that would draw visitors in, but one which also represented the individual states’ contributions to the national suffrage movement. Organizers solicited contributions from state suffrage groups and gathered the following items for the booth:

- Rhode Island sent a portrait of Susan B. Anthony which became a showcase of the booth

- Connecticut sent a collection of dolls to represent women of each of the enfranchised western states

- suffragists in Michigan pledge to send a framed suffrage map showing states where the vote had been won

- the Women’s Political Union of New York sent photographs of some of their recent public events, including a 1912 march to the state capital in Albany

- Arizona sent a banner, but suffragists in San Francisco wrote back to ask for a poster or photographs or “something a little more decorative”

- the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association built a miniature Bunker Hill monument to display at the booth, representing women’s involvement in founding the country

- Mrs. Austin Sperry (identified as the oldest member of the Susan B. Anthony Club of California) gifted a purple, white, and gold banner to the booth

- and from headquarters in Washington, DC, Alice Paul sent copies of cartoons that had been published in The Suffragist to frame and decorate the booth; in return, she asked Whittemore to send photos of the booth to publish in The Suffragist.

Things came together at the booth and Margaret Whittmore was pleased to report to Alice Paul that “Our Booth is getting very full of fine Exhibits, many of the States are admirably represented.”

Another key feature of the booth was also the brainchild of Whittemore, who came up with the idea of displaying “a large cloth sign, giving the record of the vote of every Senator and Representative in the 63rd Congress...I got the idea, to be sure, from the Cover of THE SUFFRAGIST, for February 27,” which showed a “Mrs. William Colt, Member of the Advisory Council of the Union, Explaining the Vote of N.Y. Congressmen on the Suffrage Amendment.”

Just a few weeks after Whittemore first shared the idea, the San Francisco Examiner described the giant panel displaying the suffrage voting record of “446 Congressmen” as the largest exhibit in the Educational Palace at “18x19 feet and in six columns.” The chart of the Congressmen’s votes became a centerpiece as a visual representation of CU’s sole purpose at the Expo:

All American visitors were asked to look up the record of their Congressman; to discover how he voted on the Suffrage Amendment: they were asked to sign the monster petition to Congress.

Day-to-Day Activities at the Booth

The main work at the booth throughout the summer of 1915 was gathering signatures for the grand petition to be carried across the country to President Wilson, signing up new CU members and subscribers to The Suffragist, and distributing pamphlets, buttons, pennants, and anything else the suffragists could give away to promote their organization and their cause. In response to news that Expo rules prevented the CU from increasing their fundraising efforts by selling any items from the booth, Paul recommended to Whittemore: “If you cannot sell the Suffragist on the Exposition grounds I would advise that you sell at the gates of the Exposition.”

Booth organizers also held open-air lectures and sponsored talks throughout the exposition grounds. High-profile speakers and visitors to the Congressional Union’s booth included Mary Beard, Crystal Eastman Benedict, Helen Keller, May Wright Sewall, and Secretary of State William B. Wilson. The suffragists took advantage of a steady stream of dignitaries, celebrities, and state and national politicians who visited the PPIE throughout the summer, attempting to lure prominent visitors to the booth and heavily publicizing their responses to and records on suffrage. There was even an interactive attraction when the head of the American Voting Machine exhibit invited visitors to try his machine by voting on a real issue: a mock referendum on a federal suffrage amendment. The editors of The Suffragist predicted that, “By the time the Exposition closes, the machine will have registered an honest record by which to gauge public sentiment on the amendment.”

At the same time as she was busy setting up and managing day-to-day booth activities, almost immediately after the booth opened, Alice Paul asked Margaret Whittemore to “begin work for the Conference of Women Voters. We thought the best time to have this would probably be about the end of August.” Paul may have wanted to start planning for the WVC (which was eventually held in September, not August), but first Whittemore had another idea for a summer event, proposing a large International Suffrage Meeting to coincide with the wartime gathering of the Women’s International Peace Conference at the Hague; this meeting took place at the San Francisco Expo on June 1st and 2nd, 1915.

After three months as director of the Congressional Union suffrage booth, Whittemore reported on her progress – “We have been able to procure about 400 members since the opening of the Exposition” – before leaving San Francisco and returning home to Michigan where she thought she could be more useful among the people and organizers she knew. Alice Paul just missed seeing Whittemore at the Expo as Paul arrived in California at the end of summer to help prepare for the Woman Voters’

Convention. With help primarily from Doris Stevens, Iris Calderhead of Kansas, and Elizabeth Kent of California, it was another suffragist, Ella Morton Dean, who took Whittemore’s place and took charge of day-to-day operations at the booth.

Final months of the Expo:

For the most part, after the June meeting, the emphasis for the CU at the San Francisco PPIE was on preparations for and publicizing the Woman Voters’ Convention.

From headquarters in the East, the focus of CU efforts shifted after the September WVC to preparing for the road trip envoys to reach D.C. in time for the opening of Congress in early December. In October, an overwhelmed Ella Dean asked for more help at the booth, but Paul simply said they could not afford to pay another person because of the expenses of the WVC and the road trip and the meeting in D.C. Dean suggested that “We need some special event by which to arouse enthusiasm and hold interest” at the Expo, but by then Paul had already suggested Dean cut back on activities and simply greet people who come by the booth, noting that Expo attendance in general was probably diminishing by this point late in the year anyway.

But that was not Dean’s experience. In mid-October, a month after the thrill of the WVC, she reported that “the booth meetings have been interesting and well attended,” and that she was “getting as many new members daily if not more than in any other time in the history of the Booth.” But Paul had already moved on, feeling the CU had benefited all it could from the Expo and from diverting resources to San Francisco. She instructed Dean to collect on pledges made at the WVC so they could close out the books, and asked her to send photos and cartoons from the booth back to headquarters. The San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition officially closed on December 4, 1915.

The year 1915 was an eventful one for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. The Panama-Pacific International Exposition was over, the envoys made it to Washington, D.C. with some version of the petition they began at the PPIE suffrage booth, and got their meeting with President Wilson and spoke before Congress. Just a few months later, in early 1916, the Congressional Union was transformed into the National Woman’s Party and they were on to the next phase of their strategizing

and the final push toward a national amendment.

While preparation for the Woman Voters’ Convention consumed much of the CU’s organizational energy throughout 1915, the PPIE suffrage booth itself was an important point of activity, emphasizing the voices of western women voters in the suffrage campaign, and solidifying the CU organizationally and strategically as an independent organization separate from NAWSA. Indeed, among the many conflicts between NAWSA and the CU that year, NAWSA leadership rejected the CU’s platform at the Expo’s Woman Voters’ Convention of opposing any party (including the Democrats, the party of Woodrow Wilson) that did not support the federal suffrage amendment.

As part of a 1915 U.S. tour, British suffragists and peace activists Emmeline Pethick Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence visited the PPIE in San Francisco several times and spoke at the CU suffrage booth. Impressed by the work there, Mrs. Pethick Lawrence “compared the Exposition in its breadth of scope and bigness of purpose to the [Congressional] Union and its policies.” Indeed, that “bigness of purpose” included settling for nothing less than an amendment to the U.S. Constitution protecting women’s right to vote and was certainly the vision the CU brought to a global audience at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition that year.

Further Reading:

Adams, Katherine H. and Michael L. Keene, Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign (University of Illinois Press, 2008)

Boisseau, TJ, and Abigail M. Markwyn, Gendering the Fair: Histories of Women and Gender at World's Fairs (University of Illinois, 2010)

Markwyn, Abigail M., Empress San Francisco: The Pacific Rim, the Great West, and California at the

Panama-Pacific International Exposition (University of Nebraska Press, 2004)

Smith, Sherry. Bohemians West: Free Love, Family, and Radicals in Twentieth-Century America (Heyday Books: Berkeley, 2020)

[Halloween series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. What do you think?]

______________________

“Anthony Amendment Favored at Exposition,” The Suffragist (May 1, 1915).

Alice Paul to Ella Dean, October 12, 1915, and Dean to Paul, October 13, 1915, NWP Papers, Correspondence.

Ella Dean to Lucy Burns, October 14, 1915; Alice Paul to Dean, October 13, 1915; and Dean to Paul, October 17, 1915, NWP Papers, Correspondence.

Margaret Fay Whittemore to Alice Paul, March 4, 1915, NWP Papers, Correspondence.