[In honor of Patriots’ Day,

and inspired by my book-in-progress for the American Ways

series on the history of American patriotisms, a series on that topic and

examples of critical patriotism from across American history. Leading up to

this special post on that next book project of mine!]

It's

done (a draft of the manuscript, that is)!

What, you want

to hear more? Okay, here are three more things about my next book, which I’m

hoping will be out before 2020 is done:

1)

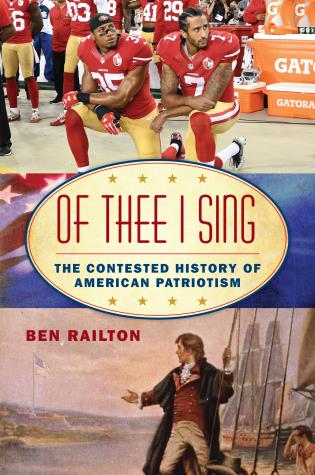

A Sequel, but Not the Same: Of Thee I Sing is in the same Rowman & Littlefield American

Ways series as was my last book, We

the People, and it would certainly be fair to describe it as a sequel,

presenting a parallel lens through which to analyze debates over American identity

(this time the spectrum between celebratory, mythologizing, active, and

critical patriotisms, rather than exclusion and inclusion). But it’s of course not

identical to that prior book, and one definite difference is in the structure:

while We the People moved roughly

chronologically, each chapter focused on a particular ethnic/cultural group;

while the eight chapters of Of Thee I

Sing focus directly on eight historical moments: the Revolution, the Early

Republic, the Civil War, the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era, the

Depression/WWII, the 60s, and the 80s (with a conclusion on the age of Trump,

natch). That meant I could explore a number of distinct histories and stories

from each time period, which helped lead to the other two elements I’ll highlight

here.

2)

Hidden Gems: One benefit of that time period

approach was that for each chapter I could in my research/reading dig deep into

that period for histories and stories that seemed to have something to do with

my focal forms of patriotism, and in the process I uncovered many that were

entirely unfamiliar to me and I have to believe are likewise relatively unknown

to most Americans. Here’s one compelling example: under the World War I-era Espionage

and Sedition Acts, a silent film about the Revolution entitled The Spirit of ’76 (1917) was seized by the government

for portraying the English (now America’s wartime allies) too harshly, and the

film’s producer, a Jewish American immigrant from Germany named Robert

Goldstein, was sentenced to ten years in prison; at the sentencing Judge

Benjamin Bledsoe told Goldstein, “Count yourself lucky that you didn’t commit

treason in a country lacking America’s right to a trial by jury. You’d

already be dead.” There’s a lot more such amazing, largely untold stories in

the book!

3)

Rethinking the Familiar: The chapters’ time

period focal points also, and I would say just as importantly, allowed me to

focus on histories with which we are all generally familiar, and reexamine them

through the lens of these debates over patriotism. That started with the very

first chapter, on the Revolution, and with a great question asked of me by series editor John David Smith.

He pushed me to think about the era’s Loyalists, which nicely lined up with my

longtime interest

in that community and sense of the Revolution as at its heart a civil war. To

that end, I argue in my Revolution chapter for the value of seeing Loyalists as

critical patriots—not quite to the United States of America, both because the

nation didn’t exist yet and because they weren’t advocating for its creation;

but to the American community of which they were just as much a part as the

Revolutionaries. That’s one example of many such reframings in Of Thee I Sing, which I can’t wait to

share with you all soon!

April Recap this

weekend,

Ben

PS. What do you

think? Other examples or forms of patriotism you’d highlight?